Climate change is a slow-to-take-effect, complex phenomenon that remains contentious among the American public with some arguing that it is a “socially” constructed rather than an objective “physical” process. Reluctance to accept climate change is partially due to the complexity of the science involved and the complications in communicating the degree to which human activity has contributed to a rise in temperatures. At the same time, it is also related to the large-scale involvement of international institutions, world celebrities as well as political and religious leaders. The number of factors and influencers involved in the debate has left plenty of room for sceptics and deniers to take advantage of the public’s natural resistance to change, which has bred complacency. As a result, there has been little action taken to slow down climate change or reduce its effects.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND TOURISM CHOICES

As citizens’ knowledge and awareness of climate change and its consequences increase, it begins to be an important consideration in everyday decision-making. Tourism is one area where climate change may have a particularly strong impact on thoughts, plans and behaviours. For example, as the frequency and intensity of storms increase, they impact on the safety and beauty of seafronts making prospective visitors less likely to choose particular leisure or holiday destinations. Without appropriate precautions, it is likely that the effects of climate change will damage the appeal of various locations and, in effect, damage the prosperity of local businesses and the well-being of local populations.

To prevent this, it is important to understand how people’s attitudes toward climate change moderate their leisure choices. A research team including three colleagues from Rosen College of Hospitality Management, Dr. Alan Fyall, Dr. Asli D. A. Tasci, and Dr. Jill Fjelstul, and Dr. Roberta Atzori from California State University, Monterey Bay, are taking the lead by examining how climate change attitudes affect the likelihood that past visitors to Florida choose this destination again. Although their findings should be treated with caution – they report the likelihood of future decision-making, which is difficult to measure – they offer tentative insights as to how climate change may affect Florida’s future.

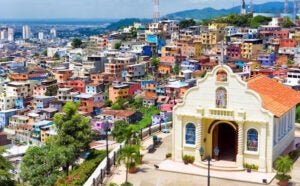

BEAUTY AND VULNERABILITY OF FLORIDA

Florida is one of the states most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. With its favorable climate and beautiful beaches, the region is understandably popular with tourists. However, as hurricanes become more common and more severe, prospective visitors may not want to vacation in an area where the seafront has lost its appealing aesthetic and where they may also fear for their safety. As Florida’s income largely depends on tourism, any decline to the number of visitors would significantly affect the state budget and the population’s livelihood.

In response, local communities across Florida have been developing and implementing adaptation measures that include, among others, installation of storm water pumps, upgrades to storm water and sewer systems, and suitable updates to building codes. However, as these efforts are being undertaken by communities without state coordination or oversight, they are sporadic and disjointed, and lack sufficient consistency.

To provide Florida with a framework for thinking about how climate change may affect the state’s future, the team of colleagues used the social representations theory to understand the likely effects of climate change on tourists choosing Florida as a holiday destination.

SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS HELP MAKE SENSE

The theory proposes that social groups develop a shared meaning of a new, unfamiliar phenomenon by aligning it with what is already a familiar and comfortable representation. These representations come from a combination of direct experience, mass media exposure and social interactions that help individuals define and organize their reality in the context of their cultural and social world. Social representations distort reality to preserve the existing preconceptions and become particularly important when dealing with issues subject to debate, like climate change. Even though these are not logical or coherent thought patterns, and are therefore full of contradictions, they may provide tentatively useful insights as to the direction in which attitudes may affect decision-making. There are three mechanisms of social representations: anchoring, objectification and personification. Anchoring is a type of cultural assimilation that makes the unknown known by relating it to an already assimilated phenomenon, which includes naming or use of metaphors, for example, describing the planet as “sick” or “on the way to die”. Meanwhile, objectification works by transforming the unknown into something concrete that a person can perceive with their senses, for example, images of people escaping floods caused by climate change that are used in mass media. A special type of objectification is personification where individuals assimilate the unknown through a person who is strongly associated with the phenomenon, for example, former American vice-president Al Gore as a stand-in for climate change.

CHANGING THEORY INTO INSIGHTS

While the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change declared warming of the global climate system as “unequivocal” with many of the changes observed since the 1950s unprecedented over millennia, doubt remains in the public’s eye. Understanding how social representations of climate change might affect tourists’ choice of destination allows particular locations to prepare for shifts in seasonal demand and to prevent changes to their regions that might become associated with discomfort or dissatisfaction.

As theory of social representations suggests that views and opinions stated in surveys reflect representations of realities that are commonly shared, the group conducted a cross-sectional survey on former Florida visitors, to explore how consequences of climate change might affect their decision to come again. Consideration was given to phenomena that included unacceptable changes to temperature, rainfall, cloud cover or wind, disappearance of beaches or increased spread of tropical disease, and others. All the phenomena chosen are well-documented consequences of climate change reported elsewhere in the world. Although no explicit reference to climate change was made in the survey, it is likely that respondents associated words and phrases with climate change nonetheless.

SURVEY RESULTS

Five hundred and nine individuals took part in an online survey, and 432 surveys were included in the final analysis, following data examination for outliers and distribution assumptions. More than half of participants were male and the median age of respondents was in the range of 25-34 years old. In the past, visitors travelled to Florida mostly to sunbathe on the beach, relax, swim, observe marine wildlife, fish or pursue water sports.

Data analysis revealed that levels of anchoring did have an effect on the declared likelihood of a repeat visit under provided scenarios. A low level of anchoring – where people declared limited worry about climate change – was associated with no change to the likelihood of visit.

At the same time, people who reported a high level of anchoring – had high concerns over climate change – were less likely to choose the same destination again. At the same time, the study detected no relationship between objectification or personification on the declared likelihood of repeat visit. In addition, social representations of climate change seemed to have no effect on the declared likelihood of repeat visit of a place with implemented adaptation measures aimed to prevent or limit climate change-related consequences.

INSIGHTS FOR FLORIDA TOURISM

In conclusion, this study suggests that attitudes toward climate change have a small effect on the projected decision to visit a destination. However, it is important to note that participants in this survey were not deterred from declaring a visit to Florida when told about climate change adaptations. This suggests that the state should not fear a concerted effort to lessen any possible damage caused by climate change. The fear is that it would keep tourists away prematurely; in fact, introduction of such adaptations might be welcomed by people highly concerned about the state of the planet, who declared they’re more likely to visit if adaptations are put in place. Nevertheless, the results of this study should be treated with caution. Analysis of projected tourist intentions offers only a small glimpse into a decision-making process and does not directly determine future behavior. In addition, study participants were not randomly selected and the sample was skewed toward a younger and lower income demographic, not necessarily representative of the average population visiting Florida. Future research should look to qualitative methods to elucidate tourist attitudes on climate change and how they may affect visits.